Habitat and Biodiversity

Wetlands provide critical habitat for a wide variety of plants, fish, amphibians, birds, and mammals.

High rates of hyporheic exchange (the mixing of surface and shallow subsurface water) in river-wetland corridors can dampen seasonal and daily temperature fluctuations in surface waters in a way that benefits fish and other aquatic organisms. Functional river-wetland corridors provide both abundant and diverse aquatic and riparian habitat and corridors for species migration.

Habitat destruction drives the decline and extinction of many species. Species living in the habitat are displaced or destroyed, reducing biodiversity. Habitat destruction can take many forms. Draining wetlands or other waterways adds to habitat destruction. Illinois has lost more than 90% of its original wetland acres. This loss is of special concern because of the important functions that wetlands perform. Changes in the climate, caused by greenhouse gas emissions, are a form of habitat destruction when it forces a species to abandon its once-suitable habitat due to rising temperatures and changing conditions.

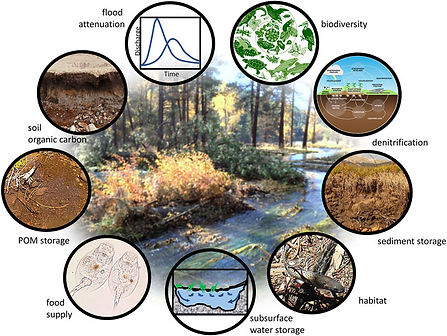

Illustration of river functions associated with river-wetland corridors. Source: "Rediscovering, Reevaluating, and Restoring Lost River-Wetland Corridors," by Ellen Wohl, Janine Castro, Brian Cluer, Dorothy Merritts, Paul Powers, Brian Staab, and Colin Thorne, Frontiers in Earth Science, June 30, 2021.

In nature, the stability and health of an ecosystem is closely tied to its biodiversity. Biodiversity refers to the number of different species present. The more diverse a community of plants and animals is, the better it is able to adapt and adjust to changes. In nature, the loss of one species could have an effect on other species. The loss of a keystone species in particular--such as beavers--has serious impacts. Keystone species are species that are vital to so many other species that they are said to hold the ecosystem together.

Following is a partial list of species of plants, insects, birds, mammals, fish, and amphibians that could benefit from an increase in river-wetlands corridors in Illinois:

-

The Eastern Prairie Fringed Orchid (Platanthera leucophaea) is federally threatened and state endangered. The eastern prairie fringed orchid (EPFO) occurs in a wide variety of habitats, from wet to mesic prairie or wetland communities, including, but not limited to sedge meadow, fen, marsh, or marsh edge. It can occupy a very wide moisture gradient of prairie and wetland vegetation. It requires full sun for optimal growth and flowering, which ideally would restrict it to grass and sedge dominated plant communities.

-

Hine’s emerald dragonfly (Somatochlora hineana) is federally and Illinois endangered. Previously thought to occur only in Lower Des Plaines watershed in Illinois, its world distribution is limited to Illinois, Wisconsin, Missouri, Michigan, and Ontario. It lives 3-5 years as an aquatic larva or nymph; as an adult it only lives a few weeks. It relies on groundwater fed wetlands with minimal competition from other surface water species.

-

The following wetlands birds were ranked by the Bird Conservation Network as having "Immediate Management Needed: Species having high regional threats and experiencing large population declines. Conservation action needed to reverse or stabilize long-term declines" or as "Species experiencing moderate to strong declines and/or threats to breeding. Management or other actions needed to stabilize/ increase populations or reverse threats: American Bittern, King Rail, Black Rail, Piping Plover, Common Tern, Least Bittern, Black Tern, Black-Crowned Night-Heron, Common Gallinule, Yellow-Headed Blackbird, Forster's Tern, Pied-Billed Grebe, and Wilson's Snipe.

-

Illinois Chorus Frog: Throughout American history, these inch-and-a-half-long, dark-spotted frogs have been known for their distinctive, high-pitched, bird-like whistles that can be heard from great distances. Often mistaken for toads because of their stout bodies, they have thick forearms used for digging burrows. Tiny frogs that spend most of their time below ground, they were once common along the wide, sandy soiled grasslands and floodplains of the Mississippi and Illinois river basins. But as a result of unbridled housing development that has eliminated lowland habitat, and agricultural practices that now level fields instead of leaving the water-holding troughs the frogs used for breeding, most of their already small populations are in serious decline. They are now listed as threatened in Illinois, but this status does not protect their habitat.

-

Blanding’s Turtle: This medium-to-large turtle is targeted by the pet trade because of its beautiful yellow chin and throat. It once ranged through much of the Great Lakes region and the northeastern United States, but the only large remaining populations are found in Minnesota and Nebraska. Blanding’s turtles have suffered extensive declines from habitat loss, road mortality and intense predation on eggs and hatchlings.

-

Eastern Massasauga rattlesnake (Sistrurus catenatus). Status: Threatened. The eastern massasauga is a small, thick-bodied rattlesnake that lives in shallow wetlands and adjacent uplands in portions of Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Michigan, Minnesota, New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, and Ontario. The eastern massasauga has been declining over the past three decades due to loss and fragmentation of its wetland habitat. Throughout its range, biologists have confirmed that less than half of the eastern massasauga’s historical populations still exist. We know of 558 historical populations, of which 211 have been lost and the status of 84 is uncertain – with the likelihood that many of those populations have also been lost. We have information indicating that 267 of the historical populations still exist today. Most of those populations are in Michigan and Ontario, Canada. New York, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Wisconsin and Iowa have fewer populations.

For More Information:

-

Checklist of Illinois Endangered and Threatened Animals and Plants

-

More Beavers Equals More Birds: In Western Montana, Birds Flock to Beaver Ponds

-

Hydrologic and Geomorphic Effects of Beaver Dams and Their Influence on Fishes

-

Alteration of stream temperature by natural and artificial beaver dams

-

An ecosystem engineer, the beaver, increases species richness at the landscape scale

.jpeg)

Success Story: Sue and Wes Dixon Waterfowl Refuge

For most of the 20th century, Hennepin & Hopper Lakes in Putnam County, Illinois, were drained to make way for cropland. But these backwater lakes in the floodplain of the Illinois River, 40 miles north of Peoria, roared back to life in 2001 when the Wetlands Initiative turned off the drainage pump and began restoration. In 2001, the Wetlands Initiative began restoration of the almost 3,000-acre site, first by turning off the pump and disabling the drain tiles. Fed by springs, seeps, and rainfall, the lake beds refilled within three months and many native species of plants and animals began to return on their own. Early restoration work focused on reestablishing native plant communities in different habitats across the site and stocking the lakes with fish.

Today the 3,000-acre Sue and Wes Dixon Waterfowl Refuge is one of the premier natural areas in the state and is open to the public 365 days a year. Where once only corn and soybeans grew, a mosaic of lakes, marshes, seeps, savannas, and prairies now supports a huge range of native flora and fauna. TWI’s goal in restoring the Dixon Refuge has been to bring back levels of biodiversity approaching what was once typical of the Illinois landscape prior to European settlement.

In 2012, the Dixon Waterfowl Refuge was officially listed as a Wetland of International Importance in accordance with the global Ramsar Convention on Wetlands. This designation recognizes the Refuge for the rare wetlands, endangered species, native fish populations, and large numbers of migratory waterfowl it supports.

More than 730 native plant species thrive at the Refuge. The site is also an Audubon Important Bird Area, with more than 270 bird species observed nesting, foraging, or resting there (download the site's bird checklist here). Thousands of migrating waterfowl use Hennepin & Hopper Lakes as a critical stopover in spring and fall. The Refuge also contains an extremely rare and high-quality seep wetland habitat.

Illinois needs more success stories like Dixon Waterfowl Refuge!